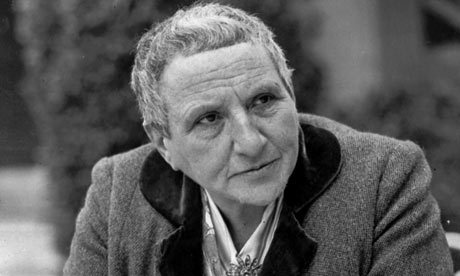

Amanda V. requested a writing prompt inspired by Yusef Komunyakaa and I'm always up for a challenge, so here you go! Komunyakaa is perhaps best known for his work dealing with his tour of duty in Vietnam from 1969-1970 — an experience that would have a vivid and indelible effect upon him for decades after the fact — as well as his life after the war. His best known poem is undoubtedly "Facing It," which deals with a visit to Maya Lin's Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., however I've chosen a different poem, one of my favorites from his collected works, to base your exercise on: "You and I Are Disappearing"

You and I Are Disappearing

The cry I bring down from the hills

belongs to a girl still burning

inside my head. At daybreak

She burns like foxfire

she burns like a piece of paper.

in a thigh-shaped valley.

A skirt of flames

dances around her

at dusk.

hanging at our sides,

We stand with our hands

while she burns

She burns like oil on water.

like a sack of dry ice.

She burns like a cattail torch

dipped in gasoline.

She glows like the fat tip

of a banker's cigar,

A tiger under a rainbow

silent as quicksilver.

at nightfall.

She burns like a shot glass of vodka.

She burns like a field of poppies

at the edge of a rain forest.

She rises like dragonsmoke

to my nostrils.

She burns like a burning bush

driven by a godawful wind.

What I find most striking about this poem is the very effective tension Komunyakaa achieves between emotional depth and tempo: the poem reads like an eternal moment, drawn out painfully and ultimately never resolved, while Komunyakaa fills that everlasting interval with great psychological resonance, carried out through a number of viscerally rich images, as well as a steady litany of "She (burns)." While it might be enough to stretch the moment out alone, or to rush through a poem built out of strong imagery, Komunyakaa weds the two techniques and the emotive power of the poem is increased exponentially — it's almost as if you could graph the poem with X and Y axes corresponding to time and emotion and come up with something like the image you see here (forgive me, more math-minded students in the workshop, there's a reason I'm an English professor).

So what I'd like you to is play around with the linked strengths of these two basic components of your poetry. You don't have to necessarily work in the way Komunyakaa does — instead, you can work with speed instead of slowness — but try to match the tempo of your poem with an appropriate emotional or imagistic gravity. To achieve this, you might want to play around with variations of things like line length, sentence length (vs. line length), stanza length, rhythm and meter, alliteration (i.e. percussive consonant sounds falling in close succession or with long pauses in-between). Breath will come into play here, as well as presentation on the page (you could work in more of an open-field mode). Especially in an intro-level workshop like this, you might put all of your focus into getting one of these facets of your poem right, but now that we're in week eight, you've had enough experience to start thinking about doing two things simultantously.