In addition to thinking about the poems you'll select for your final portfolio and chapbook, you should already be giving some thought to the design and binding for your chapbook. Hopefully the time we spent a few classes back going through a wide array of possible constructions, sizes, shapes and bindings was useful, and to help you as you more actively start planning, here are a few how-tos that might be of use:

Aside from the content of your book, you'll want to think about things like your cover materials, art and layout. The easiest and cheapest option is to buy what's called cover stock (

here's an example from Staples;

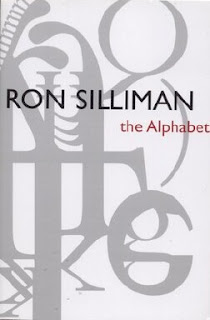

Office Depot has some different options for colors) — it's a sturdy card stock that comes in a variety of colors, from pastels and neutrals to brights, and that will pass through either a photocopier or a printer without difficulty. You might want to simply print in black on your covers, or use a combination of stamps, cut-outs glued to the cover, or embossing to create your design. A variety images will print well over this sort of stock, from simpler line drawings to photographs, or you can go with a purely textual design. An interesting compromise might be to make a design that uses only text, but manipulated in an abstract way. Ron Silliman's latest book,

The Alphabet, has a cover by Geof Huth that's constructed out of letters (see at right). Once your card stock comes out of the printer or copier it will likely have warped a little from the heat of the condenser, so stack them (waiting until they've dried if the ink hasn't set) and then put a few heavy books over them so they'll flatten out again. You might also wish to use endpapers — a single sheet of paper, often colored, patterned or textured — that goes between the cover and the interior pages. Again, browsing the aisles of your local office supply warehouse will give you some ideas for possibilities: you might wish to use a complementary color (the last book I made, for example, had bright red endpapers to liven up the ash-grey covers), or you can use vellum (tracing paper), some sort of patterned writing paper, or hell, cut sheets to fit out of the newspaper. I've always done layout for covers in PowerPoint (my favorite free and ubiquitous image compositor), which allows you to easily resize images, match them in terms of size, create and manipulate text boxes, etc. When putting your covers together, don't forget that the front will be the righthand side, the back the left.

For interior layout, here are a few recommendations. First, you can accomplish a lot in Microsoft Word, setting the page layout as landscape and then creating two columns. You have built-in rulers to measure distance from edges and widths of text, which is helpful. Be sure to leave enough breathing room around the edges of of the page, as well as on the left margin of the righthand column (for the last project I put together, I left a half-inch at both the top and the bottom, set the right margin and the space between columns at an inch each, and left a half-inch as the far-right margin). You'll want to decide upon a standard format for your chapbook: What font will you use? What size (I recommend using a 10 or 11 pt., no larger)? What size will you make your titles (you can make them the same size or increase by 2pts. of the body text)? Will you underline them? Will you center them or make them flush left? How many lines will you skip before your title, and how many between your title and the start of the poem? Finally, after you've decided on your list of poems, I wholeheartedly making two different page layouts — start by posting the title page, blank pages and poems in the order you want them to appear, simply going from column to column, and getting an idea of when and where a poem will go over to a second page, if there will be issues with margins, etc. Then save this document once under some name, and resave under a second name. Keep both documents open at the same time, and start shifting around the material so that it'll be in the order you'll want to print in. If all else fails and this becomes way too frustrating for you, it's fine to either construct a chapbook that doesn't require folding or to just print on one side of the page (technically, this is called the "recto," i.e. the righthand page; the lefthand page is the "verso").

Before printing sufficient numbers of covers and book guts to make your print run, I recommend printing just one copy and assembling it, so that you can troubleshoot problematic layouts, issues with fonts, margins, etc. Once you've made any necessary changes, then go ahead and print. When I've done these sorts of projects in the past, I've used a laserwriter printer (usually at the office I was working in) to print the covers, and have used a photocopier with duplexing capabilities to produce the necessary number of sets of book guts (note: if you opt to photocopy,

never use the photo settings — I know that it seems like it will produce a higher-quality image, but it will make your text fuzzy). One final decision you'll need to make is what paper to use. In the past, I've used thicker, higher-quality paper with a high cotton content (what's called thesis or resume paper), and this not only gives the book more heft, but also makes your pages less transparent. A box of this sort of paper can run you $30-40 however, so a few of you might want to chip in and split one, or just use regular copy paper. Think of the math this way: if you're making a 16-page book, then you're going to need 4 sheets per book, and say you're making 40 books, then that's 160 pages altogether. A ream has 500 sheets, so three of you can split a box of thesis paper, have 20 sheets leftover for screwups or damaged pages, and pay about $10 each. Or if you're making 40 24-page books (6 sheets) two of you can split a ream for $15 each.

Also, don't forget that you can literally cut your costs in half by making smaller chapbooks (two to a sheet/set of paper) and then cutting them in half with a guillotine, however this isn't for the faint of heart, and you run the risk of ruining huge amounts of your printed components with imprecise cutting. I don't recommend the guillotine for the faint of heart. And though copying and/or printing costs something there are ways around it — hit up a parent or sibling who has access to a copier or laserwriter at work, or shop around to find a cheaper option. The print shop in the basement of McMicken is relatively cheap, only a few cents a page.

In general, I recommend splitting costs if at all possible, whether that's buying a sampler of cover stock and divvying up the individual colors, splitting paper, sharing a needle and a spool of thread, or going in on a stapler together. It's also not a terrible idea to team up in terms of production. You might not believe it, but once all of your printing is done, you can put together 40 or 50 books in half an hour while watching television, but you can invite a few classmate over, and knock out all of your books in an hour then celebrate with the non-alcoholic beverage of your choice.

We can talk about the ins and outs of book production in our free time over the next few classes, and I'm more than happy to answer any questions you might have via e-mail or during my office hours as well.

Additionally, here are some supplies you might want to consider purchasing, depending on how you want to lay out your chapbooks:

Saddle/Booklet Staplers: I've looked around the web and haven't been able to find a small hand-held booklet stapler like the one I showed you in class, but here are a few relatively inexpensive options if you'd like to invest in one:

Of course, there are a number of ways you can design/bind your chapbooks that won't require a saddle stapler (including using a size smaller than 8.5 x 6.5 [i.e. standard copy paper folded in half], stapling through the edge of the cover, sewing, using elastic thread in a loop, etc.), but if you want to minimize some other complications, you'll likely need a long-reach or saddle stapler. You might also want to purchase some sort of bone folder or guitar slide, to help you make a hard crease easily and without the risk of papercuts. Here are some options on Amazon: